Psychology doesn't talk enough about culture; or, how I learned that the vagus nerve is a lie

sorry for the vagus nerve clickbait

In 2016 I got my first experience on the other side of the classroom, as a "co-instructor" for the graduate course Empathy at the University of West Georgia with Dr. Tobin Hart.

Tobin did most of the work assembling the course’s books and papers, but I suggested we add an essay by the late Philip Cushman, a theoretical and hermeneutic psychologist, called Empathy—What One Hand Giveth, the Other Taketh Away: Commentary on Paper by Lynne Layton.

Cushman ~problematizes~ empathy, which is a fun academic way of saying he calls into question our common sense understanding and use of the term. He states:

“I conclude that empathy is not a natural, instinctive process that produces an automatic result and that what therapists mean by empathy is much more a culturally formed moral virtue than a technical skill; it is not a natural, instinctive process that produces an automatic result. Therapists, patients, and society would be better served if we came to understand and appreciate the difference between virtues and skills, and confront the implications of that difference for both the politics of therapy and a therapeutic politics.”

The tl;dr to what Cushman is pointing to is that we regularly use words and ideas that we think refer to “natural” processes that produce “automatic” results. He wants to poke holes in our understanding and use of “empathy.” So what’s his takeaway?

Let’s back up. Why would I question or “problematize” empathy? Why would Cushman? Cushman was a therapist, and although I didn’t know him personally, I know people who worked with him and thought the world of him. I’m probably not such a bad person myself, according to most people who know me. So why question empathy? Isn’t empathy great, and not only great, but something we should be investing in, trying to inculcate? I remember Tobin telling me about the Roots of Empathy program designed to encourage empathic perspective-taking in children.

I’m actually not writing this to question whether we should have empathy training programs in kindergartens. Maybe that’s good, I don’t know. I can see it being a lot better than some other things kids learn. Cushman’s point, and my point, is this: we take a lot of things for granted. We assume we know what “empathy” is. Maybe we assume it’s a biological process based in mirror neurons, in which we take up and mirror the emotional/affective stance of another person (or animal). So it’s a kind of nervous system synchronization—surely involving the vagus nerve (side note, I teach a psychology of mind-body course and I’ve never once mentioned the vagus nerve in it).

That’s one possibility. Another possibility, which I think is closer to the truth (per Cushman): empathy is a cultural practice, which like all cultural practices carries with it certain invisible cultural norms and philosophical assumptions.

A brief detour may be helpful here. One of my favorite research studies, by Carolin Demuth and Heidi Keller, is the unsexily titled Cultural models in communication with infants: Lessons from Kikaikelaki, Cameroon and Muenster, Germany. In this study, they look at how mothers in these two contexts talk to and with their infants. Long story short (but do read the actual article if you’re interested—it rules), German middle-class mothers do a lot of face-to-face interactive talk, especially talk that invokes what we could call internal psychological states. Think, “how are you feeling today? Are you feeling happy?”

The Cameroonian mothers do less of this conversational-egalitarian, face-to-face, turn-taking, internally focused talk. Instead you might bounce the baby on your knee, or carry it swaddled across your back while you more unidirectionally explain and model to the child what’s expected of them in terms of appropriate socio-emotional behavior (which is also what the German mothers are doing, in their own way).

So basically, culture isn’t some abstract thing we carry around in our heads; it’s developmentally instantiated via interpersonal/social interactions from the very beginning of our lives. We’re never outside of it, and in fact it’s far more pervasive and “baked-in” than most of us recognize. It’s the foundation of our psychology, our personhood. Our personhood is not something passed down strictly through genes or nervous systems or brains. Cue the fish wondering what water is.

Empathy isn’t simply “nervous system synchronization” or some kind of mirror neuron extravaganza because we are not simply biological. Or rather we’re the kind of biological beings who are tuned for cultural development. But I actually think trying too hard to be balanced with regard to the biology-culture divide often fails to land us close enough to recognizing our essential culturality.

Like in Demuth and Keller’s article, the (western) understanding and practice of empathy is grounded in cultural and philosophical norms and assumptions—that we’re “interior” beings with interior feeling-states that must be communicated through words, in interactive processes involving a kind of turn-taking interiority-sharing. When I reflect on these things, or when I teach these ideas, I like to try to imagine how this might be different for people who don’t grow up in a culture where face-to-face, interiority-sharing is the norm. It’s not easy to do (the irony being that I’m describing empathic perspective-taking concerning other cultural ways of being a person).

If you’re one of 5 people I’ve gotten into a (hopefully not too heated) social media argument with about the biomedical model in psychology and why I’m resistant to even neurodiversity discourse, I hope this helps explain my perspective. We treat language as transparent—what some in philosophy call a correspondence theory of truth.

I think the language we use reflects and refracts our culture. That’s not to say I don’t believe in the brain or the nervous system or neurodivergence—I just think there’s an asymptotic relationship (never quite converging, if you’re like me and got a rural Texas math education) between the language we use and the material realities we’re often trying to describe.

What makes this relationship asymptotic are the invisible structures of our enculturated being. Yes, the nervous system exists. Yes, we can affect the nervous system with mindfulness practices (complicating my “asymptote” metaphor), with the words we use/how we reflexively respond to our embodied affective experience (I love and teach Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing personally).

I even think framing our experience in terms of “nervous system” affects the underlying material-biological reality! But to me, this inspires caution around what we take for granted and more importantly what we fail to see in terms of invisible cultural (and historical, political, economic…) structures that contribute to our experience of the world and ourselves.

Biology doesn’t have to make these processes and structures invisible (again I’m not some scary postmodern antirealist who thinks cells don’t exist), but a great deal of biomedical discourse, at least in the psychology world, does end up doing that.

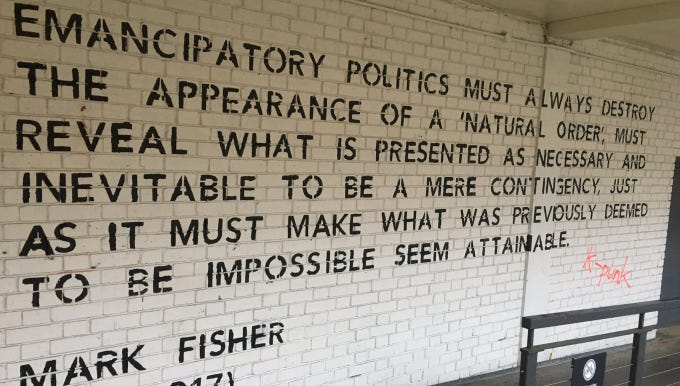

There are people who try to bridge the culture-nature divide in a way that grasps some of what I’ve been trying to describe here—people like Karen Barad—but to be honest I’m too stupid to really understand a lot of the natural science side of things; and politically I’m focused on how biomedical discourse is so often used to “naturalize” (make us think something is historically/biologically inevitable, like say masculinity or poverty or IQ) things that are actually “contingent” (dependent on things like historical and political processes, or in the case of the Demuth and Keller paper, the ongoing developmental instantiation of cultural norms contributing to personhood).

To circle back, I don’t really have a problem with empathy, but I do think it would be wise of us to understand what we’re reinforcing (a particular culture and its norms and assumptions) when we use language and ideas that emerged out of and reflects that culture—rather than thinking we’re using language handed down by God that touches the world without cultural mediation.